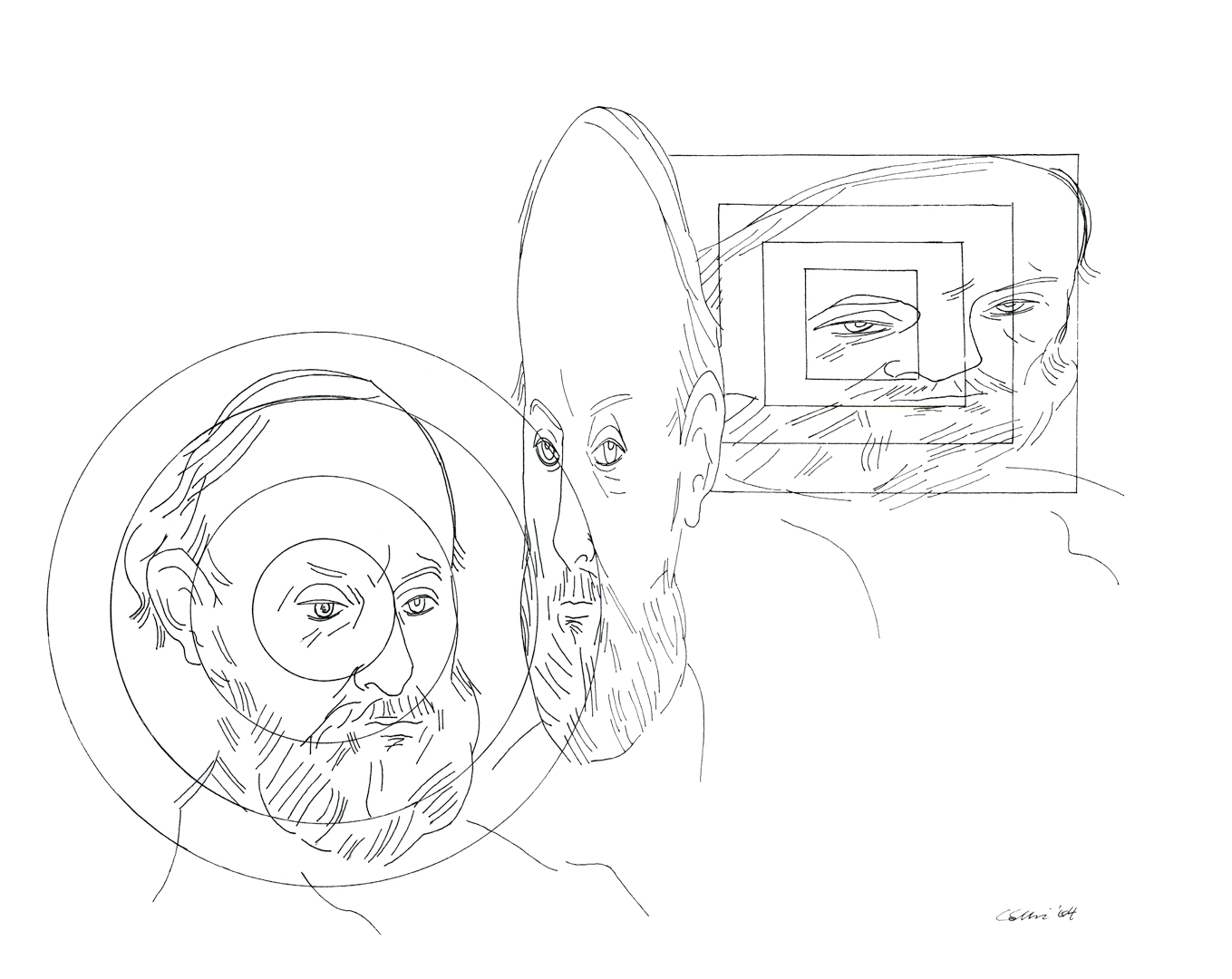

Charles A. Csuri: After Paul Cézanne

Artist(s):

Title:

- After Paul Cézanne

Exhibition:

Creation Year:

- 1964

Medium:

- Ink on paper, analogue computer

Size:

- 64 x 81 cm (25 x 32 in)

Category:

Artist Statement:

After the Artist Series

“This [technology] allowed me to systematically alter the original geometry of my drawing. One end of the pantograph device traced the drawing and the other end was simultaneously making transformations. I was intrigued with the idea of using devices and strategies to create art. I questioned the notion there had to be a tactile kinesthetic process to create a drawing or painting.”

— Charles A. Csuri

Over the centuries, many artists have sought to believably translate our three-dimensional world onto a two-dimensional surface. Csuri, like his early contemporaries who also worked as painters, defies a concern for strict realism and instead embraces the two-dimensional surface, challenging its limitations in his earliest endeavors with computer art. There were no mass-produced operating systems when Csuri began creating art in the early 1960s, necessitating that he create his own computer programs to challenge the limits of this new technology. Further, computers at this time were unable to assign values to account for mass, although the perception of spaces and their relatedness to mass will become a hallmark of Csuri’s art created in a three-dimensional world space.

In his After the Artist series, the first analogue computer art created by Charles Csuri from 1963 to 1964, Csuri recalls and recreates classic works by historically significant and personally compelling artists. In all, he created nine analogue drawings, referencing works by Paul Cézanne, André Derain, and Albrecht Dürer, among others. In this series, Csuri creatively distills selected masterpieces into their vital components, thus placing the works by these artists into a new role he has assigned to them.

Then, using his analogue process, Csuri masterfully repeats, stretches, skews, and inverts the elements. These works translate traditional art by harnessing a vehicle originally created for the scientific applications. The result is a new artistic paradigm, in which Csuri appropriates scientific elements and injects unpredictability, dynamism and controlled artistic chaos. By stripping the works of Cézanne, Derain and Dürer of their z-axis, Csuri removes that aspect which confers depth and volume, working instead with “relationships between objects as transformations involving position, rotation and scale.” These ‘transformations’ result from the distillation of well-known works into their simplified forms, and their subsequent manipulation results in tension between dimensions.

The intellectual climate of early twentieth century Paris generated schools of art such as Cubism and Fauvism, movements that sought to rebuke the photographic, mechanical reproduction of the tangible world. Their investigations into essential expressions of color and line drove artistic innovation. Here, Csuri reevaluates two of the artists who played significant roles in this milieu, Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) and André Derain (1880–1954).

In After Paul Cézanne, Csuri pays homage to Cézanne’s significant contributions to the art world, particularly his innovations as the forefather of Cubism, a style in which space is broken into planes outside traditional modes of representation. Csuri was well aware of Cézanne’s prominent role in art history and had a personal affinity for his work, having spent long hours in museums and galleries closely studying the works of Cézanne and other master artists. In a personal symbolism of geometric forms, Csuri uses concentric circles and progressively larger squares that emanate from the center of Cézanne’s eyes. Read from left to right, the circles and squares express Cézanne’s unique vision and the modes through which he translated physical space onto two-dimensional canvas. When asked about the symbolism, Csuri stated, simply and with a smile, “He was the father of modern art, having the vision for Cubism…I couldn’t resist playing with it.”