SIGGRAPH 1991: Art and Design Show

Chair(s):

- Isaac Victor Kerlow

-

- Earth Observatory of Singapore

- Pratt Institute

- Columbia University

Location:

Las Vegas, Nevada, United States of America

Dates:

July 28th - August 2nd, 1991

Art Show Overview:

Welcome to the SIGGRAPH ’91 Art and Design Show!

This year’s show continues with the SIGGRAPH tradition of showcasing some of the most outstanding visual works created with the aid of computer graphics technology. But this year’s show also has a new facet. For the first time in its history, this year’s show has two distinct components: fine arts and design.

The show is now presented as the SIGGRAPH ’91 Art and Design Show. The addition of a design category was made in light of the increasing number of submissions to the show that were never intended to be seen – or judged – as fine arts pieces, but instead were created as designs for business or communications purposes. In recent years many of these pieces were not included in the show because the show was conceived as a fine arts show instead of an event where different kinds of visual works created and produced with the aid of computer technology could be viewed. To recognize the increasing number of design submissions to the SIGGRAPH show, we expanded the show’s scope to include such works.

Isaac Victor Kerlow

Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, New York

Chairman of the SIGGRAPH ’91

Art and Design Show

Additional Documents:

-

Quotes:

View: [Quotes]

Acknowledgements:

A project of this scope required the cooperation, advice and support of many individuals and companies. We are particularly grateful to all the dedicated volunteers who helped make this project possible.

The members of the SIGGRAPH ’91 Art and Design Show Committee provided guidance, advice and support: Timothy Binkley, Eleanor Flomenhaft, Cynthia Goodman, John Grimes, Sonya Haferkorn, Kent Hunter, Tom Linehan, David Peters, Wendy Richmond, Donald Rorke, and Judson Rosebush.

Carolyn Cahill, my assistant, made valuable contributions. She attended to the many day-to-day details and organizational tasks such a project demands with intelligence, patience and humor.Many graduate students at Pratt Institute contributed to this project. Iris Benado assisted me with the space layout, and coordinated the drafting and installation of the show. HyeKyung Kim, Alexandra Lecomte, Don Noone, and Suntaree Palasingh helped with data entry, compilation of slides and background information, filing and retrieval. Ashwini Jambotkar helped with the video pre-production for all animation entries.

I am grateful to Mike Bailey and Carol Byram, SIGGRAPH ’91 co-chairs, for their trust and support. Molly Morgan-Kuhns, SIGGRAPH ’91 conference coordinator, provided invaluable help for getting things done.

I am also grateful to Tom Linehan and Mark Resch, past SIGGRAPH art show chairs, and to Richard Beach, past SIGGRAPH editor-in-chief, for their sympathy and encouragement. My job would have been much more difficult without their valuable insights.

Many companies donated time, talent, and money to make the SIGGRAPH ’91 Art and Design Show a reality. Their contributions are recognized by the ACM/ SIGGRAPH community.

The following companies contributed towards the production costs of this publication: Apple Computer, SOFTIMAGE, RasterOps, and Wavefront Technologies. Special recognition goes to Goodsight Images in New York City for donating much of their color and imagesetting services.

Isaac Victor Kerlow

Exhibition Artworks:

-

1789: A Salute to the French Revolution

[Cornell University Publications Services]

Categories: [Design] -

1990 Brazilian Ball Poster

[Taylor & Browning Design Associates]

Categories: [Design] -

1991 Type Calendar

[Adobe System Marketing Communications]

Categories: [Design] -

24-Hour Turnaround

[Mark Anderson Design]

Categories: [Design] -

A Decade of Innovation

[IBM San Jose Design Center]

Categories: [3D & Sculpture] [Design] -

A Volume of Two-Dimensional Julia Sets

[Daniel J. Sandin]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

Abstract

[Chiara Boeri]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Adobe Systems Incorporated 1989 Annual R...

[Adobe System Marketing Communications]

Categories: [Design] -

Afga Compugraphic Macintosh-Based System...

[Pentagram]

Categories: [Design] -

Air India

[Landor Associates]

Categories: [Design] -

All But The Obvious

[SOS]

Categories: [Design] -

An Exercise in Utilities

[Macworld Magazine]

Categories: [Design] -

APO Knife

[Uro Designs]

Categories: [3D & Sculpture] [Design] -

Apocalypse Then

[Michael King]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Audi 100/200 Brochure 1990

[SHR Design Communications]

Categories: [Design] -

Audio Ballerinas

[Benoit Maubrey]

Categories: [Performance] -

BCE Place Office Interior

[Design Vision Inc.]

Categories: [Design] -

Beautiful World

[Margo Chase Design]

Categories: [Design] -

Borrowings #1

[Sean Nixon]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Breakfast Attempt

[Michael Klug] [John Underkoffler]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Breathing Room

[Mark Neumann]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

Building As Sign

[Landor Associates]

Categories: [Design] -

Cages

[R/Greenberg Associates]

Categories: [Design] -

Calendar Clock

[Reed Design]

Categories: [Design] -

Chain Bridge Bodies

[Kenneth Snelson]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Chindi Frieze #4

[Don P. Miller]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Columbus Page

[design : Weber]

Categories: [Design] -

Configuration

[Tessa Elliot]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

Corporate Presentations Promo

[TW Design]

Categories: [Design] -

Cyber-All-Night-Rave

[Cyberdada]

Categories: [Design] -

Cyberdada Manifesto Video

[Cyberdada]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

Data Safety

[Macworld Magazine]

Categories: [Design] -

Design and Advertising into the 90s

[Pentagram]

Categories: [Design] -

Design Circus

[design : Weber]

Categories: [Design] -

Disintegration #13

[Eva K. Sutton]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Downtown Manhattan Map

[Wiggin Design Inc.]

Categories: [Design] -

Dual

[Dean Randazzo]

Categories: [Installation] -

End

[Seton Coggeshall]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

Envisioning Information

[Edward Tufte]

Categories: [Design] -

Equilibrium #A

[Hui-Chu Ying]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Escape Club

[Margo Chase Design]

Categories: [Design] -

ESSE by Gilbert

[THIRST]

Categories: [Design] -

Female Monarchy

[Lisa A. Moline]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Festival of Festivals 1990

[Reactor Art + Design]

Categories: [Design] -

Finger Paint

[Ken Goldberg]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

First Among Equals: A Visual Critique of...

[Jeff Gates]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Floating Series #3

[Diane Fox]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

From Easel to Machine

[Az-zet]

Categories: [Design] -

From Stone to Bone

[Susan Ressler]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Fun With Computers

[Reactor Art + Design]

Categories: [Design] -

Going For Goldfish

[Susan Alexis Collins]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

Graphika

[Waters Design Assoc.]

Categories: [Design] -

Helmet Package

[Lisa Levin Design]

Categories: [Design] -

Hotel Hankyu International

[Pentagram]

Categories: [Design] -

Hyatt Hotels Corporate Identity Program

[Landor Associates]

Categories: [Design] -

I Las Vegas

[Stephen Axelrad]

Categories: [Installation] [Interactive & Monitor-Based] -

Iceclif

[Darcy Gerbarg]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Innovation Systems Summit

[Crocker Inc.]

Categories: [Design] -

inside

[Suponwich Somsaman]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

Intertrans Annual Report

[Sullivan Perkins]

Categories: [Design] -

JCH Calendar

[M plus M Incorporated]

Categories: [Design] -

La Difunta Correa

[Claudia Vera]

Categories: [Installation] -

Lipton 100th Anniversary Tea Tin

[Primo Angeli Inc.]

Categories: [Design] -

Loft Design

[Zero One]

Categories: [Design] -

Machinedreams

[Jill Scott]

Categories: [Installation] [Interactive & Monitor-Based] -

Manuscript 42

[John S. Banks]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Marbelizing a Void (Image 1)

[Jennifer Steinkamp]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Marin Ballet Nutcracker

[Sackett Design]

Categories: [Design] -

Meltdown

[Jeff Jaffers]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

Mystery Street

[Thomas Porett]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

NEC CD-ROM

[Liska and Associates Inc.]

Categories: [Design] -

NY Art Directors Club 1991 International...

[Pentagram]

Categories: [Design] -

Omen

[Eduardo Kac]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Organic Building Corp. Promotion

[Z Communication]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

Out of Body

[Jack Cliggett]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Passage

[Gene Cooper]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

Phage

[Michael Tolson]

Categories: [Installation] -

Putti

[Eve Mosher]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Radius Inc. 1990 Annual Report

[The Design Work]

Categories: [Design] -

Random Access Memories

[Barbara Nessim]

Categories: [Installation] [Interactive & Monitor-Based] -

Random Face Generator

[Peter Voci]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

Reconstruction

[Annette Weintraub]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

ROOT

[Char Davies]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

SAND

[Char Davies] [Daniel Langlois]

Categories: [Installation] -

Santa Monica Place Design Criteria

[The Office of Reginald Wade Richey]

Categories: [Design] -

Santa Monica Place Design Criteria Eatz

[The Office of Reginald Wade Richey]

Categories: [Design] -

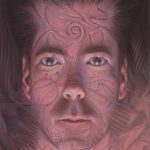

Self Portrait

[Erol Otus]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Separating With Pain

[Kathleen Ruiz]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Set Type in Your Sleep

[Mark Anderson Design]

Categories: [Design] -

Setting a Course for Leadership in Globa...

[Pentagram]

Categories: [Design] -

Sharpvision

[R/Greenberg Associates]

Categories: [Design] -

SHR Christmas Card

[SHR Design Communications]

Categories: [Design] -

Song (from the series Opera Arias)

[Azuma Kawaguchi] [Akihiko Matsumoto]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Soul of Light

[Semannia Luk Cheung]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Spector Report

[Patterson Wood Partners]

Categories: [Design] -

Spirals

[Masa Inakage]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

Sports Car

[Evans & Sutherland Computer Corp.]

Categories: [Design] -

Spruce

[Gordon Lescinsky]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Sun Watch

[Texas Instruments]

Categories: [Design] -

Superanimism

[Jason White] [Richard Wright]

Categories: [Animation & Video] -

Symmetry

[SOS]

Categories: [Design] -

Systeme Lunaire

[Jean-Pierre Hébert]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

Temple Illusions

[Jean M. Ippolito]

Categories: [2D & Wall-Hung] -

The AART Group

[Sackett Design]

Categories: [Design]

1

2

Next ›

Last »

Exhibition Writings and Presentations:

-

Title:

Bonsai

Author(s):

Category: Paper

Abstract Summary:

We are currently witnessing the end of an artistic world. Artists of tomorrow will no longer produce works but something yet to be named. They will no longer create objects but rather types of microuniverses in perpetual evolution.

These universes will be woven with uninterrupted changes, with mobile networks of lines, surfaces, forms, and forces in constant interaction, produced by the coupling of mathematics and calculators. From fractal dragons to cellular automata, from zooids to logic viruses, mathematical beings move and metamorphose in their symbolic spaces. They can change or alter the very laws by which they are constituted. They can provide the virtually autonomous substance of a new, intermediary art. The metaphor of the “symbolic bonsai” has been chosen to render the intermediary “life” of this intermediary art. Why intermediary art?

In an attempt to explain art using the words of language, even the greatest minds diverge to some extent. According to Plato, for example, art is the quest for “likelihood;” according to Hegel it aims to “reveal the truth.”Should art seek likelihood or truth? Is the artist a magician or a prophet? What, in fact, is truth? Plato said truth is a “divine vagabondage,” which undoubtedly is why it remains beyond the reach of art, why he contends we must be satisfied with a “likely” imitation.

Since we are not gods, we cannot “vagabond;” we need laws. And this need applies to art. Thus, art must also be a science. As a product of human activity, art must obey rules inherent to the techniques used to create it. But art is also sensible representations, and as such refuses the domination of abstraction and laws. The best way to resist laws is to change them—constantly. Art itself must therefore be change—perpetual change.

[View PDF]Title: Superanimism: The practice of formalised imagery

Author(s):

Category: Paper

Abstract Summary:

This essay discusses the dichotomy between visual, animated images and the abstract computer program that generates them. This digital and numerical base adds an extra dimension to the animation, whereby the creative experience is divided into a number of different levels.

Digital images are informed by the status of their algorithmic source, creating in the viewer a kind of numerical perception, thereby introducing scientific knowledge into our understanding of the visual. But because of the computer’s formalism and arbitrariness, the relation between algorithmic source and the electronic visual effect is not stable. Imagery is of a different experiential type to logical structures, and this causes their disjuncture or alienation, although they are logically and deterministically connected. Thus synthetic images do not appear “human” or manmade but objective or “natural,” like photographs.

The underlying algorithm is so contingent that in terms of being an accessible entity it hardly exists at all without reference to its sensory manifestations. The actual substance of the animate is diffused into so many different levels at once, it loses its ontological identity. These effects lead to a description of a computer animation as an object able to vitalize both tangible and intangible spaces and become a super-animate.

[View PDF]Title: The Emperor's New Art?

Author(s):

Category: Paper

Abstract Summary:

Premature over-promotion of any and all “artwork” created with computers has caused art critics to feel as if they are being asked to admire the Emperor’s New Clothes. At the same time, computer artists accuse art critics of being uninformed, myopic, and hopelessly out of touch with the new media concerns.

Artists visiting computer art shows disdain the oft-exhibited science fiction grotesqueries masquerading as art: Bad critical reception is said to be because of this “nerd” aesthetic. On the other hand, technical-minded factions also wonder when computer artists will actually learn to program, or produce something besides canned paint system imagery and indecipherable bad video tapes. Such squabbling and shifting of the blame from one group to the next is not the way to correct the problem.

Adding to the problem is the fact that standards by which we have evaluated computer art have evolved outside of the “high art” community and tend to be too low. Often the concepts of science and tools of technology are merely appropriated and exhibited as art without true artistic transformation or social context. Furthermore, when work refers to contemporary art world trends, it often does so as a form of imitation or serves merely to reinforce what we already know about image making. Without true understanding of either art or science and technology, this work can hardly help being superficial.

We need to fairly evaluate work using standards as high as those by which the rest of the arts are judged. We need to extend beyond the isolation of our small community and address broader issues. Most importantly, we need to take advantage of the uniqueness of computing and push its properties to their limits. Only as these issues are addressed and resolved will computer art gain in significance and authenticity.

[View PDF]