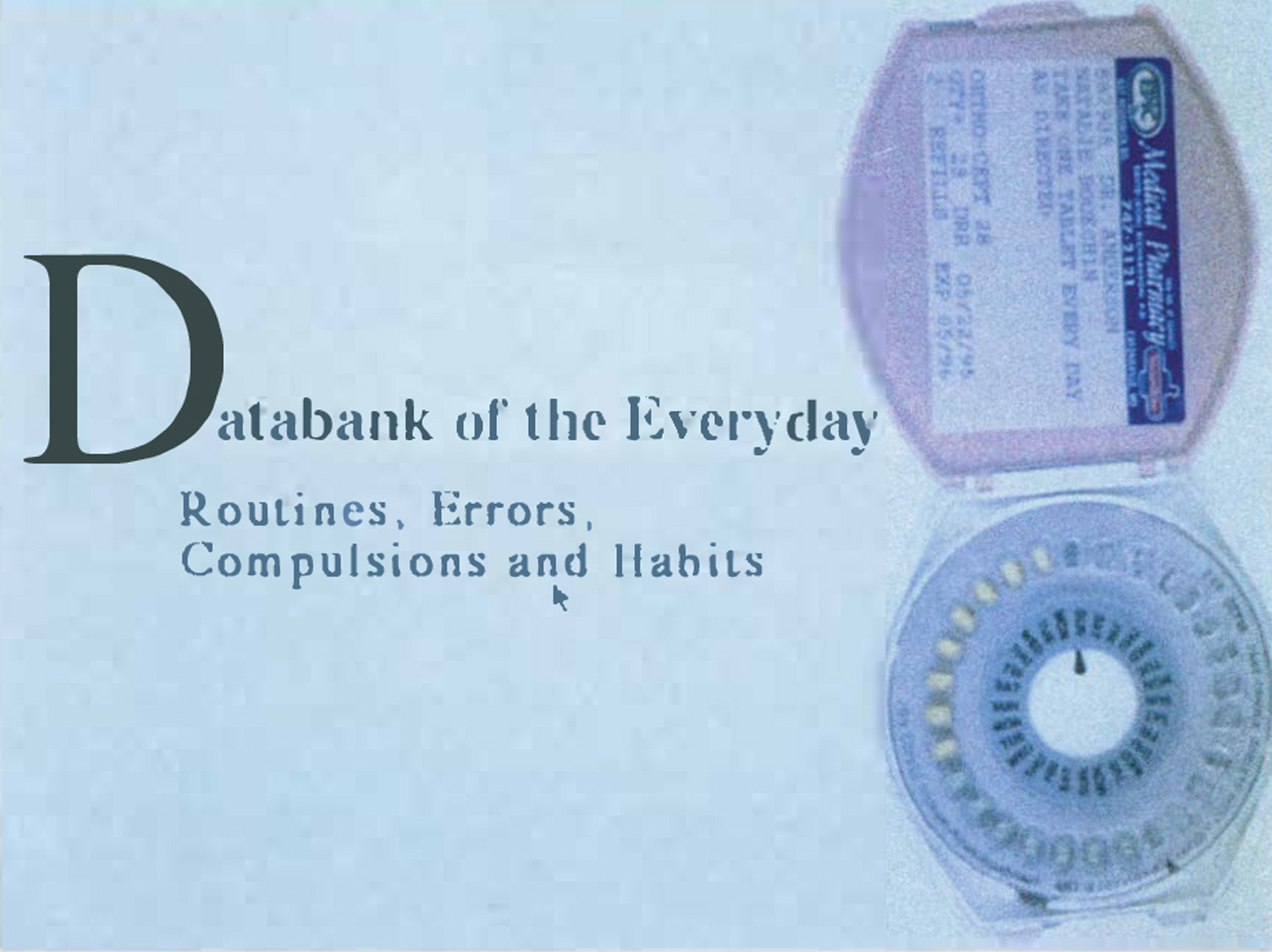

Natalie Bookchin: Databank of the Everyday

Artist(s):

Title:

- Databank of the Everyday

Exhibition:

Creation Year:

- 1996

Category:

Keywords:

Artist Statement:

Databank of the Everyday takes as its subject the real everyday uses of computers in our culture: storage, trans-mission, dissemination, and filtration of bodies of information. The work reflects on what media – from photography to computers – have always attempted to do: represent the truth of life and organize it into well-defined lists and categories.

Photography, for example, begins and ends its history with the idea of the catalog, from William Henry Fox Talbot’s inventories to the recent proliferation of electronic image banks. And so, picking up where photography left off, the Databank provides a conclusive catalog of an ordinary life. It models itself after commercial data banks with their generic all-encompassing categories such as People at Leisure, Flowers, Nine to Five, and Nature. The Databank‘s categories are no less all-encompassing and include Wasting Time, Nervous/Bad Habits, Because of My Mother, and Staged for the Camera.

The Databank proposes that everyday life consists of a series of loops performed by the body, much like the simple loops performed by a computer program. The ordinary body is like an imperfect machine, flawed in its efficiency by its desires, habits, and compulsions. The Databank can be thought of as a catalog of flawed movement studies of the everyday (scratching, shaving a leg, watching TV, and slamming a door), standing in opposition to historical movement studies of Muybridge, Marey, Taylor, and the Gibreths.

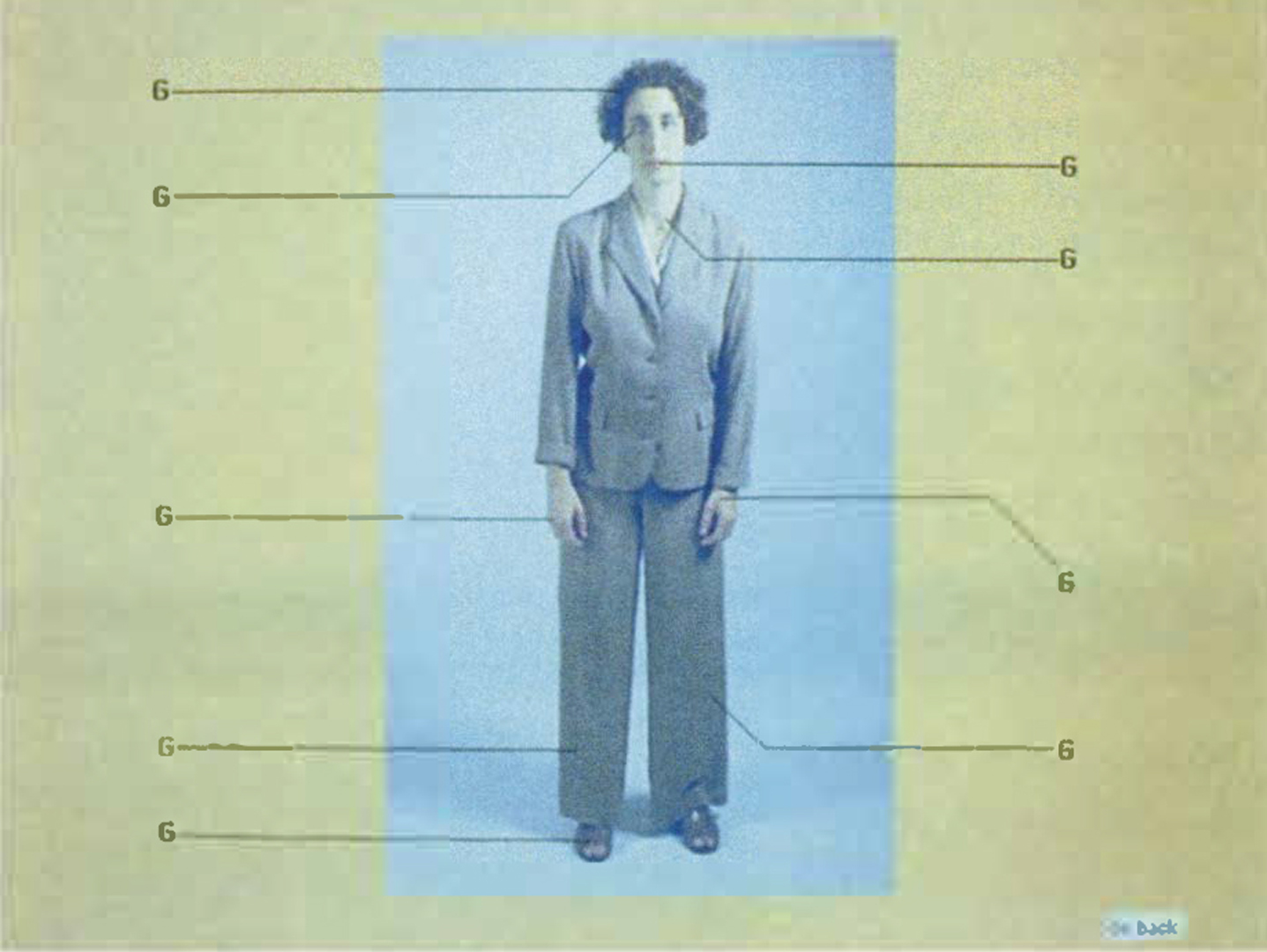

The primary graphic interface of the Databank is a loop that spins as users move between sections. The selections allow access to the same data in different ways. One section is a subject catalog featuring a diagram of the subject that animates as if in a spasm as her buttons are pressed, triggering access to a loop. Another section is a dictionary of loops with a number of miniature actions that take place simultaneously, choreographed by the user. Yet another organizes the data as antonyms. It presents such actions as pressing up and down on an elevator button, and taking a shirt off and putting it on.

Featuring the latest in amplified fin-de-siècle rhetoric, the work vehemently perpetuates the current hysteria surrounding new technologies. Again we witness a revolution, and again we hear loud claims about the universality of the change and the transformation of everyday life. (History, as we know, also repeats itself like a loop.) And so in keeping with the tradition, the Databank heralds its very own 21st-century manifesto, in compliance with early-20th-century avant-garde movements.

As digital media replaces film and photography, it is only logical that the computer program’s loop should replace photography’s frozen moment and cinema’s linear narrative. Databank of the Everyday champions the loop as a new form of digital storytelling; there is no true beginning or end, only a series of loops with their endless repetitions, halted only by a user’s selection or a power shortage.